Eugen Weber, France: Fin de Siècle

Negative Perceptions of the Fin de Siècle

With hindsight we can see that the First World War brought down the frames of institutions, ways of life and mind, that had been long crumbling. But there was no knowing this before the nineteenth century ended, before the twentieth century faced the possibility of a worldwide war. After that war was over it became fashionable to refer to the years preceding it as the Belle Epoque, and to confuse that period with the fin de siècle, as if the two were one. Perhaps they were; the bad old times are always somebody's Belle Epoque. But the Belle Epoque, named when looking back across the corpses and the ruins, stands for the ten years or so before 1914. These also had their problems, but relatively they were robust years, sanguine and productive. The fin de siècle had preceded them: a time of economic and moral depression, a great deal less redolent of buoyancy or hope.

With hindsight we can see that the First World War brought down the frames of institutions, ways of life and mind, that had been long crumbling. But there was no knowing this before the nineteenth century ended, before the twentieth century faced the possibility of a worldwide war. After that war was over it became fashionable to refer to the years preceding it as the Belle Epoque, and to confuse that period with the fin de siècle, as if the two were one. Perhaps they were; the bad old times are always somebody's Belle Epoque. But the Belle Epoque, named when looking back across the corpses and the ruins, stands for the ten years or so before 1914. These also had their problems, but relatively they were robust years, sanguine and productive. The fin de siècle had preceded them: a time of economic and moral depression, a great deal less redolent of buoyancy or hope.

And yet a lot took place during these two decades that made life better for a lot of people. Not for all. Better alternatives for the many easily turn into less choice for the few. New aspirations can be perceived as threats, especially when the aspiring begin to raise their voices. Transitions can be diversely recognized: as promise, or as menace. Different social groups see the same phenomenon differently. Even beneficent changes can be troubling: access to better food may stir regrets for the old, rough familiar fare; telephones invade privacy; swifter, cheaper transport frightens and pollutes; shorter working hours forecast idleness. Coarse sensualists welcomed the time of modern comforts succeeding "to periods of force and magnificence," delighted to think that it would go down in history as "the century of water closets, bathrooms, and central heating."1 Sterner observers deplored the softness and the laxness that the new facilities evoked. Coming too thick and fast upon one another, such impressions could be taken for evidence of present corruption, or omens of imminent decay. That is how some of the most articulate among contemporaries perceived and presented them, in the lurid context of military defeat, political instability, private adversity, public scandal, and clamorous social criticism, to stress the fin in fin de siècle that made it sound like an unhappy end.

This is what caught my eye about the circumstances: the discrepancy between material progress and spiritual dejection reminded me of our own times. So much was going right, even in France, as the nineteenth century ended; so much was being said to make one think that all was going wrong. That need not be surprising. Public discourse turns mostly about public matters--especially politics; and the style of politics calls for catastrophic imagery. A great deal of political debate either takes place on the brink of doom or envisions it looming on the horizon. Doom loomed more clearly in fin de siècle France than almost anywhere else at the time. Since contemporary interpreters and later historians pay special attention to politics, this colors their impression and ours of years when, as in most times, politics played only a small role on the surface of events. As one shrewd observer of his country put it, "politics does not hold in our lives the place it takes up in the newspapers, in [social] conversations, in the apparent existence of a nation. The public life of a people is a very small thing compared to its private life."2

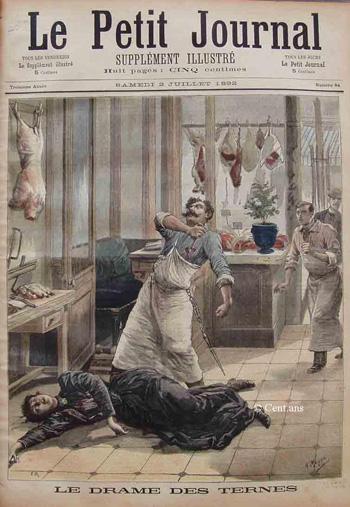

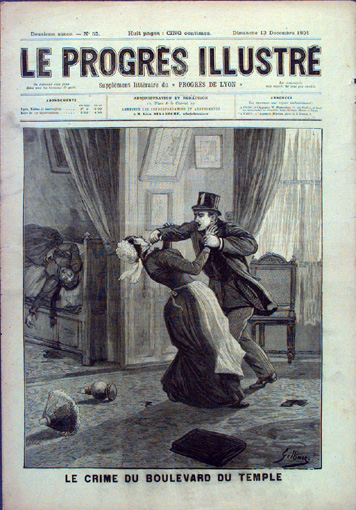

Let me say at once that public life is far from irrelevant, because  decisions made at the public level can powerfully affect the private one. Political ideas, though, remained the passion or plaything of small elites, until cheap print and popular illustrations extended them to all. During the last quarter of the nineteenth century political interests and ideologies came to stimulate the general public--more general than it had ever been--pervading popular attitudes and expectations, hence the eventual orientation of the land itself.

decisions made at the public level can powerfully affect the private one. Political ideas, though, remained the passion or plaything of small elites, until cheap print and popular illustrations extended them to all. During the last quarter of the nineteenth century political interests and ideologies came to stimulate the general public--more general than it had ever been--pervading popular attitudes and expectations, hence the eventual orientation of the land itself.

The harsh realities of universal suffrage, long eluded, were coming home to roost: lower and lower sections of the middle classes were ruling in parliament; setting the pace in society, letters, arts; tarring politics, so long a sport for gentlemen, with their vulgar brush. The populace, losing respect for their natural betters, bayed for its turn at the troughs of power. The disorderly, volcanic nature of city mobs was nothing new. The claims of organized labor, its disruptive strikes, the politics of socialism in Chamber, Senate, even the Cabinet, were more disquieting. The deferential society tottered. There was no knowing how long it would take to wane.